Planning your race season: Periodization Part 2.

How does each pre-season, event, training week and day evolve to being mapped-out and put into action? Periodization.

How does each pre-season, event, training week and day evolve to being mapped-out and put into action? Periodization.

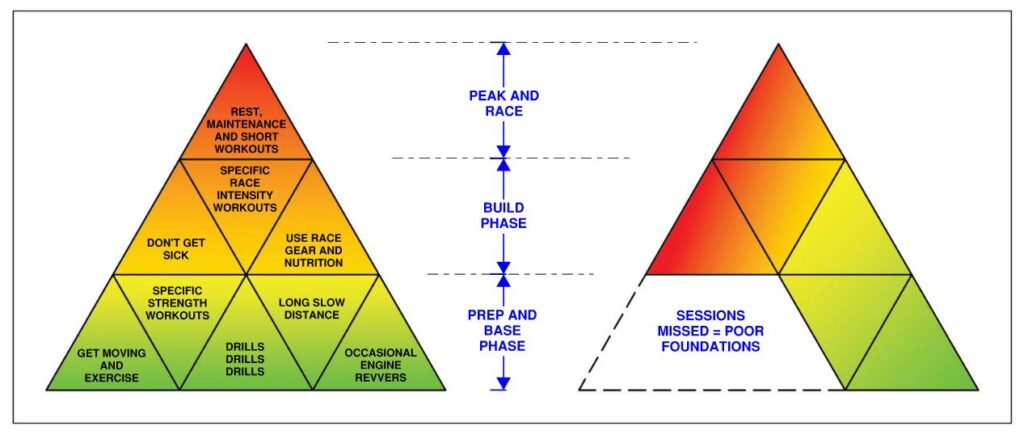

Here’s Part 2 of my advice on Periodization. I’ll use a construction metaphor, in line with my diagrams below. If you want to build a house, you need a solid foundation. It’s the one thing you cannot safely scrimp on. The diagram on the left shows how the pyramid [or house] is built on a nice wide BASE. This is your aerobic training, or LSD Phase (No I haven’t lost it… that means Long Slow Distance) and this would make up roughly 80% of the workouts in the first half of the programme – give or take. The remaining 20% would be what I call ‘Engine-revvers’ and technique. On the right, you can see the pyramid is dangerously precarious because a lot of the early preparation and base workouts have been missed. If an athlete thinks it’s only the huffing and puffing workouts that make a fast athlete – while missing a lot of the base work – some huge potential is being squandered. If you don’t know how we burn fuel at different intensities go ahead and read Different zones, different fuel. But assuming you do, remember that the first thing an endurance athlete needs to conquer is burning fat for fuel. This is honed in LSD workouts and takes 8-12 weeks for the body to learn before it’s ready for some more intense training. This is how periodization begins to anchor everything.

If an athlete doesn’t take the Base Phase seriously as part of their periodization, they are heading straight into higher intensity workouts which train the body to burn carbohydrates (sugars). These athletes are training themselves to burn the one fuel that can easily and quickly run out, hugely reducing performance and risking bonking during each workout and race. Silly huh? I would also [while removing my sarcasm] point out that if an athlete only ever does the huffing and puffing, not only are they risking injury and burning the wrong fuel but fighting an uphill battle to retain that speed. You don’t have to look far to find evidence of age group and even some elite athletes who don’t start their high end speed work until 8-10 weeks from an event. You simply can’t maintain speed for long periods. I once heard an elite triathlete say she loves going back to resting, base and recovery because slowly building the intensity back up is like shining up an old penny. The act of resting before adding steady and intense workouts in a plan leaves no stone un-turned. Remember our right hand pyramid above?

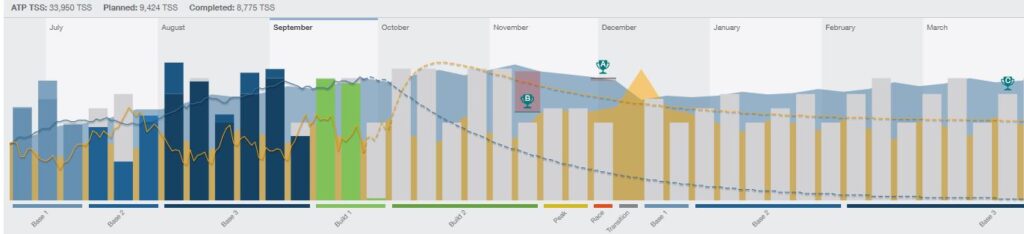

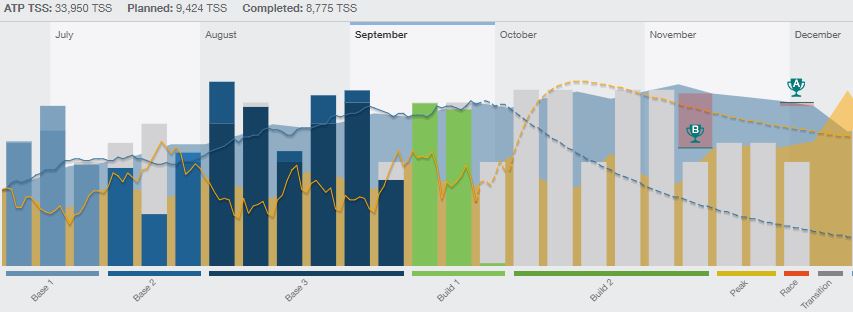

So let’s go through the Miso in detail. Below I have set out a common approach to an ‘A’ Priority Event which adds up to around 6 months of commitment. My common approach is for age groupers to have 3-week blocks – i.e. 2 weeks of work and one week of recovery – because these athletes are more prone to injury and over-training. If an athlete is not prone to injury and has a history of endurance sport, these blocks can easily be 4 weeks long.

- Preparation – Time TBD

- Base 1 – Three Weeks

- Base 2 – Three Weeks

- Base 3 – Six Weeks

- Build 1 – Three Weeks

- Build 2 – Six Weeks

- Peak – Two Weeks

- Race – One Week

- Down Time – Time TBD

As discussed above, the twelve weeks of Base training revolve around building [strangely enough] Base Endurance. In addition, this is a good time to carry out some specific weight training for swim, bike, and run as well as completing many and myriad technique drills in all three disciplines to improve efficiency and imprint the best patterns. Swimming drills would rate highest for importance – especially after some weeks out of the water – followed by running and then cycling.

Next up in our periodization, there are nine weeks dedicated to ‘Build’. Returning to the construction metaphor… what happens after the foundations? That’s right… you begin putting together elements that resemble the end product. In the case of each individual training programme there is a big switch at this point for all race distances. Now we begin specific workouts that focus on the Race Day requirements. For Standard (Olympic) Distance athletes the Build Phase contains weekend workouts that practice being at threshold with intervals and brick sessions. The volume also starts to drop as the intensity gets higher. For Full Ironman athletes, the opposite is the case as we increase volume over time and the engine-revvers barely punctuate the weeks’ sessions. By the end of the Build Phase, an athlete will be well-prepared for the discomfort of the A Race demands; whether that’s a lot of puffing or a lot of time… or anywhere between.

If we adopt the ‘2 weeks on / 1 week off’ approach, the third week can be called “Cut Back and Confirm” whereby time trials and other event-specific test workouts are used to confirm and/or adjust training zones. Although this isn’t so important during the Base Period, it is key information to gather during the Build Phase – you will see in my pyramids above that I have shown the second half of the programme fading from orange to red: this period should be the most specific for your event. To be race-specific, we must train in the correct zones… and finding the correct zones means testing. Orange and red also means being the best athlete you can be… that doesn’t just mean completing all your workouts (that’s assumed by the way). This means eating, resting and maintaining the best you can. You might want to become a complete germaphobe too – something COVID has taught us all about – as getting sick during this twelve week period would have serious impacts to your training and race day success.

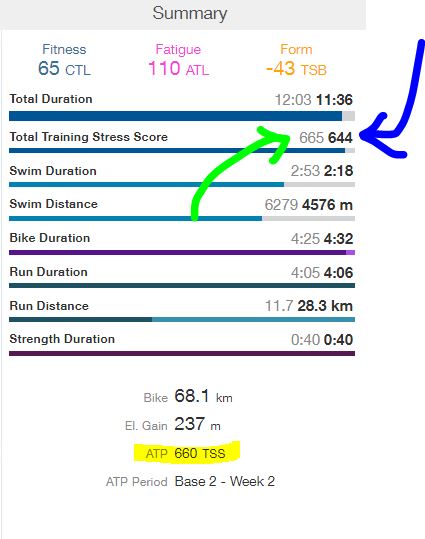

You should be under no illusion that you’re getting fitter in the last 3 weeks before Race Day. Sorry to burst your bubble A Types, but if you think you can throw loads of heart beats and calories into these three weeks in the vain hope that your success will grow… you are wrong. I use the Annual Training Plan (ATP) in Training Peaks to give athletes a clear graphical representation of what is happening during all of the Phases, but most importantly to highlight what MUST happen during the Peak Fortnight and Race Week: fatigue must drop and form must rise. Sadly, for fatigue to drop, so must fitness so the training programme should be so well planned that this drop is allowed for by ‘Aiming Above’. Now you can hopefully see that blindly ploughing through weekly training sessions without consideration for timing and purpose will not yield your best results. We must pay attention to what the workouts are for, and how our building blocks come together over a good few months.

The ATP within Training Peaks is the first time the Macro plan impacts on the workouts: each week requires a certain amount of work which TP describes as TSS (Training Stress Score). From then on, the coach should ensure the Micro plan – each and every training day – contains enough work to keep the fitness ramping up. The blue single line is the athlete’s fitness and the golden area shows how the athlete’s form should also ramp up in time for the A Race. The Holy Grail is that golden area peaking on Race Day! Have a look below and you can clearly see how the A, B and C races punctuate the 10-month time-frame.

There is a word that starts with ‘T’ and rhymes with ‘Paper’ and I avoid it like the plague. In my view… the last three weeks are about regularly revving the engine specifically for how you need to perform on Race Day. This typically means some brick sessions every few days, ensuring lots of rest. The ‘T word has so many connotations among the community that this period is somehow linked to taking the foot off the pedal. If you need three weeks of rest before your event you simply have not trained properly and are most likely over-trained, meaning you need a few weeks to recover. This can have athletes arriving at the race course feeling stale, out of practice, and demotivated… not a good recipe for a great race. The opposite is to drop volume right down but while also giving the athlete regular experience of how the race intensity should feel. I personally found [and hear the same from others often] that doing this through brick sessions really enhances the feeling that form is rising and fatigue is dropping. You start to feel like a ‘proper’ triathlete and the muscles become fresher.

Race week is more about maintenance than training. I would prescribe short, sharp race-specific sessions almost every day with some days off for travel and/or planning. A light massage, checking gear and nutrition, bike servicing etc. can all happen in the final week. To be clear, we are talking swims of just a few hundred metres and brick sessions hovering around an hour.

Book-ending the main six-month process, you will also see that there are unspecified periods for preparation and down time. These can be very personal timelines… preparation may include some strength work, being involved in other sports or even re-hab for an injury. The main aim of this period is to become prepared to embark on a structured training programme again. Any involvement in other sports should be ‘exercise’ and NOT ‘training’… there is a big difference.

Down Time [called Transition in TP] is a recovery period taken before you are willing to think about the next ‘A’ race or commencing a programme. From personal experience, I found that putting a date on this recovery period can often lead to diving back in (quite literally) to a training programme too soon. You may put 4 weeks of full recovery (i.e. being lazy and eating cheese) into your periodization and find that you’re simply not in the head space to start again after this period. Forcing yourself to start back into training can lead to tiredness, low motivation and resentment of the sport which of course we don’t want. I would recommend recovery for as long as is needed based upon feel… when you wake one morning and the short ride to work gives you the urge to happily ride for another 2 hours you’re probably ready to get going again.

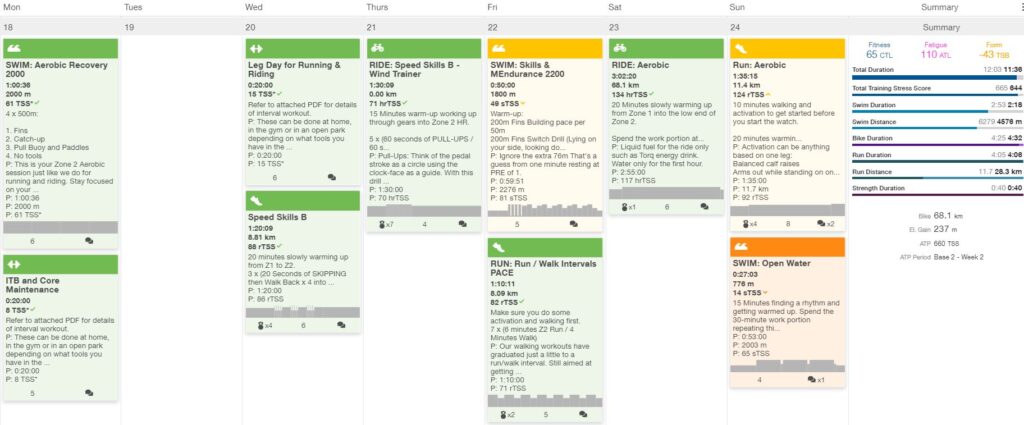

So we’ve touched on the Macro and the Miso, let’s see how the Micro is approached. These are the daily workouts that make up each week in an athlete’s calendar. I’ll continue with my Training Peaks examples as they provide the best graphics to explain. I’ve chosen a week from a Base Phase:

You can see that this particularly diligent athlete had a very good week for “Compliance”; no surprises for guessing that the green workouts are that colour because the person achieved the required Training Stress Score. Other things to notice are that this athlete often had a planned day off on a Tuesday and was currently injured, hence the run/walk workout. Again, perhaps predictably among anyone who knows triathletes that the weekend focused around aerobic rides and runs with an open water swim to round out the seven days.

My favourite area of critique before, during and after a training week is the column on the far right. As an additional piece of data to the Traffic Light colour system, these bar charts tell me exactly what was planned and what was completed. Finally, there are three numbers I look at which refer to the overall Miso Plan (ATP) for this 6-month period: The graph tells me the following umbrella view information:

- The amount of TSS recommended in the Annual Training Plan [to keep the fitness level on track for race day] YELLOW

- The amount of TSS prescribed within the training programme, GREEN and;

- The amount of TSS the athlete actually completed, BLUE

Now I would call that a very successful week of training. Don’t forget this is MICRO; acknowledging inherent tolerances within the sports watch, the software, and assumptions of intensity for each workout, a few TSS dropped or gained each week will – as they say – “All come out in the wash.”

I hope most of that makes sense. As usual, give me holler if you would like a chat or you can ask questions below.

W.

Good article! We are linking to this particularly great content on our site.

Keep up the good writing.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up!

I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back

in the future. All the best

That’s great to hear thank you! Be sure to sign up for regular notifications of new articles. W